Most people think Jesus died for theological reasons.

They’re wrong.

He died for economic ones.

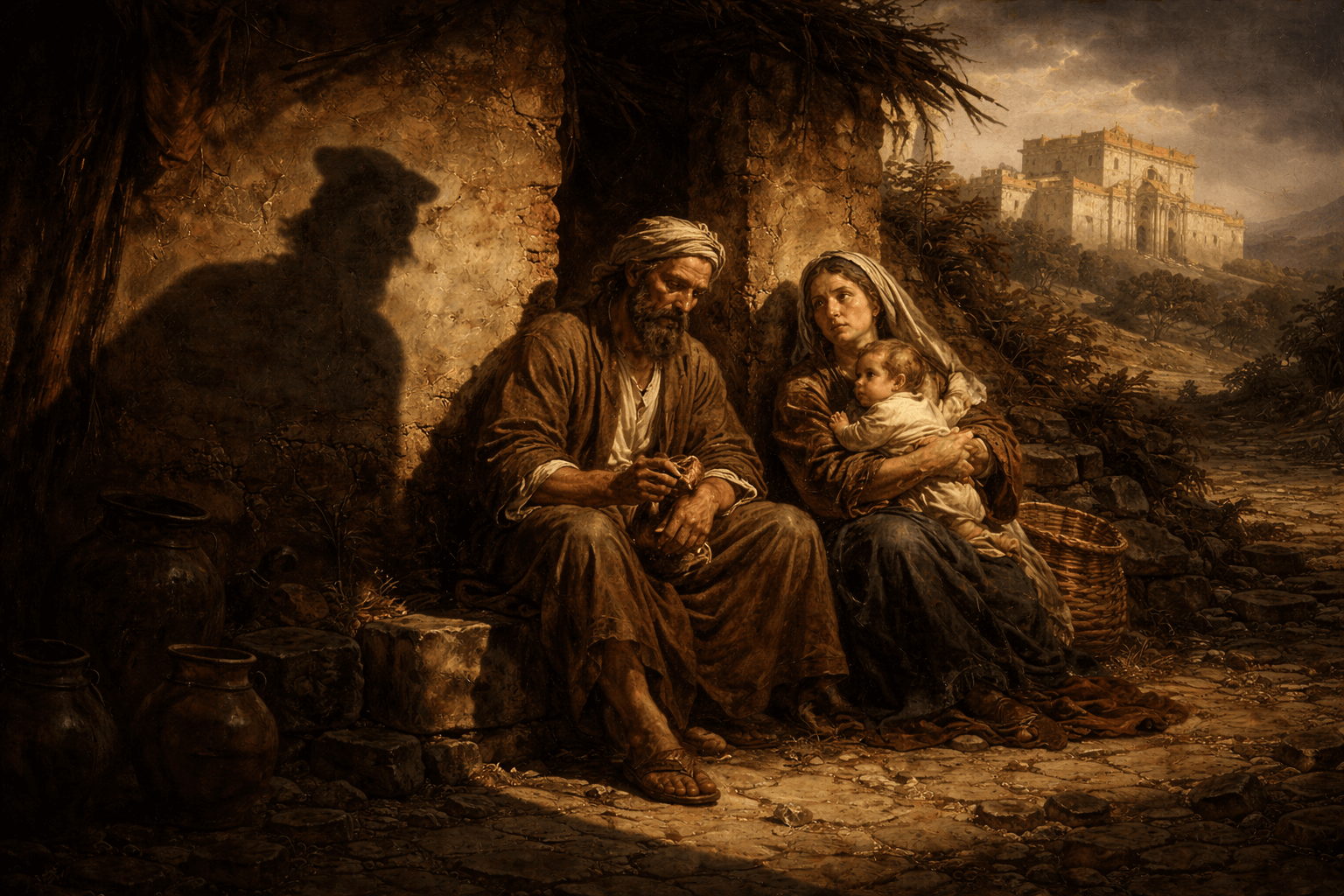

We picture sandals. Sermons. Miracles.

We imagine a spiritual world. Distant. Religious. Safe.

But the people living there?

They weren’t thinking about theology.

They were thinking about money.

Or more precisely—the lack of it.

Here’s what nobody tells you about first-century Judea.

Rome didn’t conquer territories to improve them.

Rome conquered territories to drain them.

Grain. Silver. Labor.

Everything flowed one direction.

Toward Rome.

Judea was one of those edges. A province. A resource.

And Rome didn’t care if it bled.

Most families lived on tiny plots of land.

Not farms in the modern sense.

Just enough soil to survive.

A bad harvest didn’t mean lower profits.

It meant hunger.

And here’s the part that should make you angry:

Taxes were owed regardless.

You paid because you existed.

Land tax. Produce tax. Head tax. Toll taxes on roads. Religious taxes layered on top.

Miss a payment?

No appeals process.

No bankruptcy.

No mercy.

Tax collection was outsourced.

Local contractors paid Rome upfront for the right to collect.

Then they squeezed the population to recover costs.

And make profit.

Read that again.

Abuse wasn’t a flaw in the system.

It was the incentive.

Couldn’t pay?

You borrowed.

The cycle looked like this:

Farmer plants crops.

Weather turns.

Harvest fails.

Taxes still due.

Farmer borrows from a wealthy lender.

Interest piles up.

Next year—barely survives.

Debt remains.

Eventually the land is seized.

The farmer becomes a tenant on what used to be his own property.

Or worse.

He disappears entirely.

This wasn’t an accident.

It was architecture.

Over time, land consolidated into fewer hands.

Large estates replaced small plots.

Wealth clustered around elites.

The majority sank.

The economy didn’t just produce poverty.

It reproduced it.

Generation after generation.

And there was no safety net.

None.

If you lost your land, there was no unemployment support. No welfare. No public housing.

Families were the only buffer.

When too many people fell at once?

The system offered nothing.

Now here’s where it gets uncomfortable.

The temple.

Most people imagine the Jerusalem Temple as purely religious.

Prayer. Sacrifice. Spiritual authority.

But in economic terms?

The temple was one of the most powerful financial institutions in the region.

It didn’t just shape belief.

It moved money.

A lot of money.

Every Jewish male paid a yearly temple tax.

Not optional.

Not symbolic.

Enforced.

And it had to be paid in a specific coin—the Tyrian shekel.

Local currency? Not accepted.

Roman coins? Not accepted.

Which meant money changers.

Which meant fees.

Which meant another hand in your pocket on the way to God.

Pilgrims needed animals for sacrifice.

Doves. Lambs. Cattle.

Sold at temple-approved prices.

If you were poor?

You didn’t escape.

You paid smaller offerings.

But you still paid.

Religion wasn’t replacing the Roman tax burden.

It was stacked on top of it.

And here’s the tension nobody talks about:

The temple elite were appointed with Roman approval.

High priests weren’t chosen by spiritual merit.

They were chosen for stability.

Cooperation mattered more than justice.

So the institution that claimed moral authority over the people?

It benefited from the same extraction that impoverished them.

The temple preached forgiveness.

Its operations reinforced debt.

The temple preached holiness.

Its system demanded payment.

Access to God required money.

Purity required offerings.

Forgiveness required sacrifice.

Sacrifice required coins you didn’t have.

People noticed.

By the first century, resentment toward temple authorities was everywhere.

Not because people rejected faith.

Because they saw hypocrisy.

The institution meant to protect them looked like another arm of elite control.

This is the world Jesus walked into.

And this is what most modern readers miss:

When he talked about debt forgiveness, people didn’t hear a metaphor.

They heard survival.

When he talked about release, they heard relief.

When he talked about the poor, they didn’t imagine distant charity cases.

They imagined themselves.

Their neighbors.

Their children.

The word “forgiveness” in that world?

It didn’t just mean emotional peace.

It meant debt cancellation.

Reset.

Escape.

And then came the moment that changed everything.

Jesus walked into the temple.

He saw the money changers.

He saw the system that monetized access to the sacred.

And he flipped the tables.

Not a gentle correction.

A confrontation.

He called it a den of robbers.

Not because money existed.

Because extraction had replaced justice.

Rome tolerated prophets.

Rome tolerated critics.

Rome even tolerated troublemakers.

What Rome didn’t tolerate was instability.

And temple authorities knew—unrest near Passover, when Jerusalem filled with pilgrims, was dangerous.

Crowds plus grievance equals rebellion.

From their perspective, Jesus wasn’t just preaching.

He was disrupting flows.

Challenging legitimacy.

Destabilizing the balance that kept them in power and kept Rome satisfied.

Here’s the crucial point everyone misses:

The conflict wasn’t primarily theological.

It was economic.

It was political.

The system could tolerate suffering.

It could tolerate inequality.

What it couldn’t tolerate was a narrative that made people question why the suffering existed.

And whether it was necessary.

Because once people stop accepting debt as destiny?

Extraction becomes harder to enforce.

Jesus didn’t lead an army.

He didn’t promise tax reform.

He didn’t redistribute land.

He did something more dangerous.

He undermined the moral logic that made extraction feel inevitable.

Deserved.

Divinely sanctioned.

By treating debt as misfortune rather than moral failure.

By offering forgiveness outside institutional payment.

By making the poor central rather than defective.

He destabilized something Rome needed as much as legions.

Legitimacy.

Empires can survive suffering.

They struggle when people stop believing suffering is the price of order.

Within a generation, Judea erupted.

Full-scale revolt.

By 70 AD, Jerusalem was under siege.

The temple—economic, religious, political center of Jewish life—was destroyed.

Stone by stone.

Treasury looted.

Priesthood erased.

Hundreds of thousands killed or displaced.

Rome won.

Decisively.

Violently.

But winning territory isn’t the same as winning meaning.

The system Jesus critiqued didn’t vanish after the temple fell.

But neither did his critique.

Small communities formed.

Shared resources.

Mutual aid.

Debt relief within the group.

Loyalty based on belief—not land, bloodline, or status.

These weren’t revolutions.

They were parallel logics.

Ways of living inside the empire without belonging to its moral economy.

Rome crushed armed rebellion quickly.

Always did.

But this kind of challenge was harder to extinguish.

It didn’t require temples.

It didn’t require treasuries.

It moved with people.

It worked under pressure.

It survived loss.

By the fourth century, something strange happened.

Rome didn’t eliminate this alternative framework.

It absorbed it.

The empire quietly conceded something profound:

Authority could no longer rest on force alone.

Moral credibility mattered.

Even to power.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth.

Systems don’t collapse because they’re unjust.

They collapse when the narratives justifying them stop working.

Rome optimized extraction for centuries.

But it never repaired the moral breach that made its dominance feel natural.

Economic systems wrapped in moral language are extraordinarily durable.

They survive hardship.

They survive resentment.

They survive rebellion.

What they don’t survive?

Widespread disbelief.

The moment people stop accepting that suffering is necessary.

Deserved.

Meaningful.

History doesn’t repeat.

But it exposes patterns.

And once you see how power defends itself—not just with force, but with stories—

It becomes much harder to believe those stories are accidental.

Rome had legions.

Jesus had a story.

The legions are dust.

The story is still being told.

Here’s what the empire never understood.

You can crush a rebellion.

You can destroy a temple.

You can seize land and collect every coin.

But you cannot kill an idea that sets people free.

Jesus looked at a system designed to break the poor and said:

You are not your debt.

You are not your failure.

You are not forgotten.

He didn’t come for the comfortable.

He came for the crushed.

Two thousand years later, empires rise and fall.

Economic systems still wrap themselves in moral language.

People still get told their suffering is necessary. Deserved. Meaningful.

And the Gospel still says no.

If you’re buried under a system that doesn’t see you—

If you feel like a number, a resource, an edge to be drained—

You’re not forgotten.

You’re exactly who he came for.

The temple fell.

Rome fell.

The message didn’t.

And it won’t.

This post was inspired by Financial Historian on YouTube. Their video “The Economy of Jesus’ Time” opened my eyes to see what I’d always read spiritually—through an economic lens. Thank you for helping us understand the world Jesus actually walked into. The weight of the Gospel hits different when you feel the weight of the system it confronted.